On the Internet, the Domain Name System (DNS) associates various sorts of information with so-called domain names; most importantly, it serves as the "phone book" for the Internet: it translates human-readable computer hostnames, e.g. en.wikipedia.org, into the IP addressesmail exchange servers that accept e-mail for a given domain. In providing a worldwide keyword-based redirection service, DNS is an essential component of contemporary Internet use.

that networking equipment needs for delivering information. It also stores other information such as the list of

Uses

The most basic use of DNS is to translate hostnames to IP addresses. It is in very simple terms like a phone book. For example, if you want to know the internet address of en.wikipedia.org, DNS can be used to tell you it's 66.230.200.100. DNS also has other important uses.

Pre-eminently, the DNS makes it possible to assign Internet destinations to the human organization or concern they represent, independently of the physical routing hierarchy represented by the numerical IP address. Because of this, hyperlinks and Internet contact information can remain the same, whatever the current IP routing arrangements may be, and can take a human-readable form (such as "wikipedia.org") which is rather easier to remember than an IP address (such as 66.230.200.100). People take advantage of this when they recite meaningful URLs and e-mail addresses without caring how the machine will actually locate them.

The DNS also distributes the responsibility for assigning domain names and mapping them to IP networks by allowing an authoritative server for each domain to keep track of its own changes, avoiding the need for a central registrar to be continually consulted and updated.

History of the DNS

The practice of using a name as a more human-legible abstraction of a machine's numerical address on the network predates even TCP/IP, and goes all the way to the ARPAnet era. Back then however, a different system was used, as DNS was only invented in 1983, shortly after TCP/IP was deployed. With the older system, each computer on the network retrieved a file called HOSTS.TXT from a computer at SRI (now SRI International). The HOSTS.TXT file mapped numerical addresses to names. A hosts file still exists on most modern operating systems, either by default or through configuration, and allows users to specify an IP addresshostname (eg. www.example.net) without checking the DNS. As of 2006, the hosts file serves primarily for troubleshooting DNS errors or for mapping local addresses to more organic names. Systems based on a hosts file have inherent limitations, because of the obvious requirement that every time a given computer's address changed, every computer that seeks to communicate with it would need an update to its hosts file. (eg. 192.0.34.166) to use for a

The growth of networking called for a more scalable system: one that recorded a change in a host's address in one place only. Other hosts would learn about the change dynamically through a notification system, thus completing a globally accessible network of all hosts' names and their associated IP Addresses.

Paul Mockapetris invented the DNS in 1983 and wrote the first implementation. The original specifications appear in RFC 882 and 883. In 1987, the publication of RFC 1034 and RFC 1035RFC 882 and RFC 883 obsolete. Several more-recent RFCs have proposed various extensions to the core DNS protocols. updated the DNS specification and made

In 1984, four Berkeley students — Douglas Terry, Mark Painter, David Riggle and Songnian Zhou — wrote the first UNIX implementation, which was maintained by Ralph Campbell thereafter. In 1985, Kevin Dunlap of DEC significantly re-wrote the DNS implementation and renamed it BIND (Berkeley Internet Name Domain, previously: Berkeley Internet Name Daemon). Mike Karels, Phil Almquist and Paul Vixie have maintained BIND since then. BIND was ported to the Windows NT platform in the early 1990s.

Due to its long history of security issues, several alternative nameserver/resolver programs have been written and distributed in recent years.

How the DNS works in theory

The domain name space consists of a tree of domain names. Each node or leaf in the tree has one or more resource records, which hold information associated with the domain name. The tree sub-divides into zones. A zone consists of a collection of connected nodes authoritatively served by an authoritative DNS nameserver. (Note that a single nameserver can host several zones.)

When a system administrator wants to let another administrator control a part of the domain name space within his or her zone of authority, he or she can delegate control to the other administrator. This splits a part of the old zone off into a new zone, which comes under the authority of the second administrator's nameservers. The old zone becomes no longer authoritative for what comes under the authority of the new zone.

A resolver looks up the information associated with nodes. A resolver knows how to communicate with name servers by sending DNS requests, and heeding DNS responses. Resolving usually entails iterating through several name servers to find the needed information.

Some resolvers function simplistically and can only communicate with a single name server. These simple resolvers rely on a recursing name server to perform the work of finding information for them.

Understanding the parts of a domain name

A domain name usually consists of two or more parts (technically labels), separated by dots. For example wikipedia.org.

- The rightmost label conveys the top-level domain (for example, the address en.wikipedia.org has the top-level domain org).

- Each label to the left specifies a subdivision or subdomain of the domain above it. Note that "subdomain" expresses relative dependence, not absolute dependence: for example, wikipedia.org comprises a subdomain of the org domain, and en.wikipedia.orgwikipedia.org. In theory, this subdivision can go down to 127 levels deep, and each label can contain up to 63 characters,[1] as long as the whole domain name does not exceed a total length of 255 characters. But in practice some domain registries have shorter limits than that. comprises a subdomain of the domain

- A hostname refers to a domain name that has one or more associated IP addresses. For example, the en.wikipedia.org and wikipedia.org domains are both hostnames, but the org domain is not.

The DNS consists of a hierarchical set of DNS servers. Each domain or subdomain has one or more authoritative DNS servers that publish information about that domain and the name servers of any domains "beneath" it. The hierarchy of authoritative DNS servers matches the hierarchy of domains. At the top of the hierarchy stand the root nameservers: the servers to query when looking up (resolving) a top-level domain name (TLD).

Iterative and recursive queries:

- An Iterative query is one where the DNS server may provide a partial answer to the query (or give an error). DNS servers must support non-recursive queries.

- A recursive query is one where the DNS server will fully answer the query (or give an error). DNS servers are not required to support recursive queries and both the resolver (or another DNS acting recursively on behalf of another resolver) negotiate use of recursive service using bits in the query headers.

The address resolution mechanism

In theory a full host name may have several name segments, (e.g ahost.ofasubnet.ofabiggernet.inadomain.example). In practice, in the experience of the majority of public users of Internet services, full host names will frequently consist of just three segments (ahost.inadomain.example, and most often www.inadomain.example).

For querying purposes, software interprets the name segment by segment, from right to left, using an iterative search procedure. At each step along the way, the program queries a corresponding DNS server to provide a pointer to the next server which it should consult.

As originally envisaged, the process was as simple as:

- the local system is pre-configured with the known addresses of the root servers in a file of root hints, which need to be updated periodically by the local administrator from a reliable source to be kept up to date with the changes which occur over time.

- query one of the root servers to find the server authoritative for the next level down (so in the case of our simple hostname, a root server would be asked for the address of a server with detailed knowledge of the example top level domain).

- querying this second server for the address of a DNS server with detailed knowledge of the second-level domain (inadomain.example in our example).

- repeating the previous step to progress down the name, until the final step which would, rather than generating the address of the next DNS server, return the final address sought.

The diagram illustrates this process for the real host www.wikipedia.org.

The mechanism in this simple form has a difficulty: it places a huge operating burden on the root servers, with each and every search for an address starting by querying one of them. Being as critical as they are to the overall function of the system such heavy use would create an insurmountable bottleneck for trillions of queries placed every day. The section DNS in practice describes how this is addressed.

Circular dependencies and glue records

Name servers in delegations appear listed by name, rather than by IP address. This means that a resolving name server must issue another DNS request to find out the IP address of the server to which it has been referred. Since this can introduce a circular dependency if the nameserver referred to is under the domain that it is authoritative of, it is occasionally necessary for the nameserver providing the delegation to also provide the IP address of the next nameserver. This record is called a glue record.

For example, assume that the sub-domain en.wikipedia.org contains further sub-domains (such as something.en.wikipedia.org) and that the authoritative nameserver for these lives at ns1.en.wikipedia.org. A computer trying to resolve something.en.wikipedia.org will thus first have to resolve ns1.en.wikipedia.org. Since ns1 is also under the en.wikipedia.orgns1.en.wikipedia.org requires resolving ns1.en.wikipedia.org which is exactly the circular dependency mentioned above. The dependency is broken by the glue record in the nameserver of wikipedia.org that provides the IP address of ns1.en.wikipedia.orgbootstrap the process by figuring out where ns1.en.wikipedia.org is located. subdomain, resolving directly to the requestor, enabling it to

DNS in practice

Caching and time to live

DNS in the real world

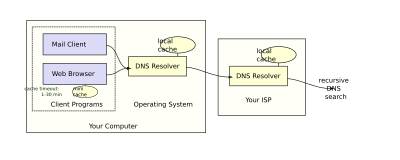

Users generally do not communicate directly with a DNS resolver. Instead DNS resolution takes place transparently in client applications such as web browsers, mail clients, and other Internet applications. When a request is made which necessitates a DNS lookup, such programs send a resolution request to the local DNS resolver in the operating system which in turn handles the communications required.

The DNS resolver will almost invariably have a cache (see above) containing recent lookups. If the cache can provide the answer to the request, the resolver will return the value in the cache to the program that made the request. If the cache does not contain the answer, the resolver will send the request to a designated DNS server or servers. In the case of most home users, the Internet service provider to which the machine connects will usually supply this DNS server: such a user will either have configured that server's address manually or allowed DHCP to set it; however, where systems administrators have configured systems to use their own DNS servers, their DNS resolvers point to separately maintained nameservers of the organization. In any event, the name server thus queried will follow the process outlined above, until it either successfully finds a result or does not. It then returns its results to the DNS resolver; assuming it has found a result, the resolver duly caches that result for future use, and hands the result back to the software which initiated the request.

Broken resolvers

An additional level of complexity emerges when resolvers violate the rules of the DNS protocol. Some people have suggested[citation needed] that a number of large ISPs have configured their DNS servers to violate rules (presumably to allow them to run on less-expensive hardware than a fully compliant resolver), such as by disobeying TTLs, or by indicating that a domain name does not exist just because one of its name servers does not respond.

As a final level of complexity, some applications such as Web browsers also have their own DNS cache, in order to reduce the use of the DNS resolver library itself. This practice can add extra difficulty to DNS debugging, as it obscures which data is fresh, or lies in which cache. These caches typically have very short caching times of the order of one minute. A notable exception is Internet Explorer; recent versions cache DNS records for half an hour.

Other DNS applications

The system outlined above provides a somewhat simplified scenario. The DNS includes several other functions:

- Hostnames and IP addresses do not necessarily match on a one-to-one basis. Many hostnames may correspond to a single IP address: combined with virtual hosting, this allows a single machine to serve many web sites. Alternatively a single hostname may correspond to many IP addresses: this can facilitate fault tolerance and load distribution, and also allows a site to move physical location seamlessly.

- There are many uses of DNS besides translating names to IP addresses. For instance, Mail transfer agents use DNS to find out where to deliver e-mail for a particular address. The domain to mail exchanger mapping provided by MX records accommodates another layer of fault tolerance and load distribution on top of the name to IP address mapping.

- Sender Policy Framework and DomainKeys instead of creating own record types were designed to take advantage of another DNS record type, the TXT record.

- To provide resilience in the event of computer failure, multiple DNS servers provide coverage of each domain. In particular, more than thirteen root servers exist worldwide. DNS programs or operating systems have the IP addresses of these servers built in.

The DNS uses TCP and UDP on port 53 to serve requests. Almost all DNS queries consist of a single UDP request from the client followed by a single UDP reply from the server. TCP typically comes into play only when the response data size exceeds 512 bytes, or for such tasks as zone transfer. Some operating systems such as HP-UX are known to have resolver implementations that use TCP for all queries, even when UDP would suffice.

Extensions to DNS

EDNS is an extension of the DNS protocol which enhances the transport of DNS data in UDP packages, and adds support for expanding the space of request and response codes.

(From wikipedia)

No comments:

Post a Comment